“During a time when the world is on edge, art can do wonders”

Anita Rogers, owner of an eponymous Manhattan gallery, talks about the art world amid pandemic and what it’s like to exhibit her late father’s drawings.

Although Anita Rogers has reopened for business to the public, very few visitors have come to her eponymous lower-Manhattan art gallery.

“The SoHo streets are mostly empty, as many of the residents have moved out of the city center, and tourists are not in town like they usually are in August,” said Rogers, who grew in Greece, Turkey, Italy, and England and is an accomplished singer. “In a typical year, most walk-ins in August are tourists, as our locals head out in late summer for the Hamptons or on other travels. We miss our August tourists this year.”

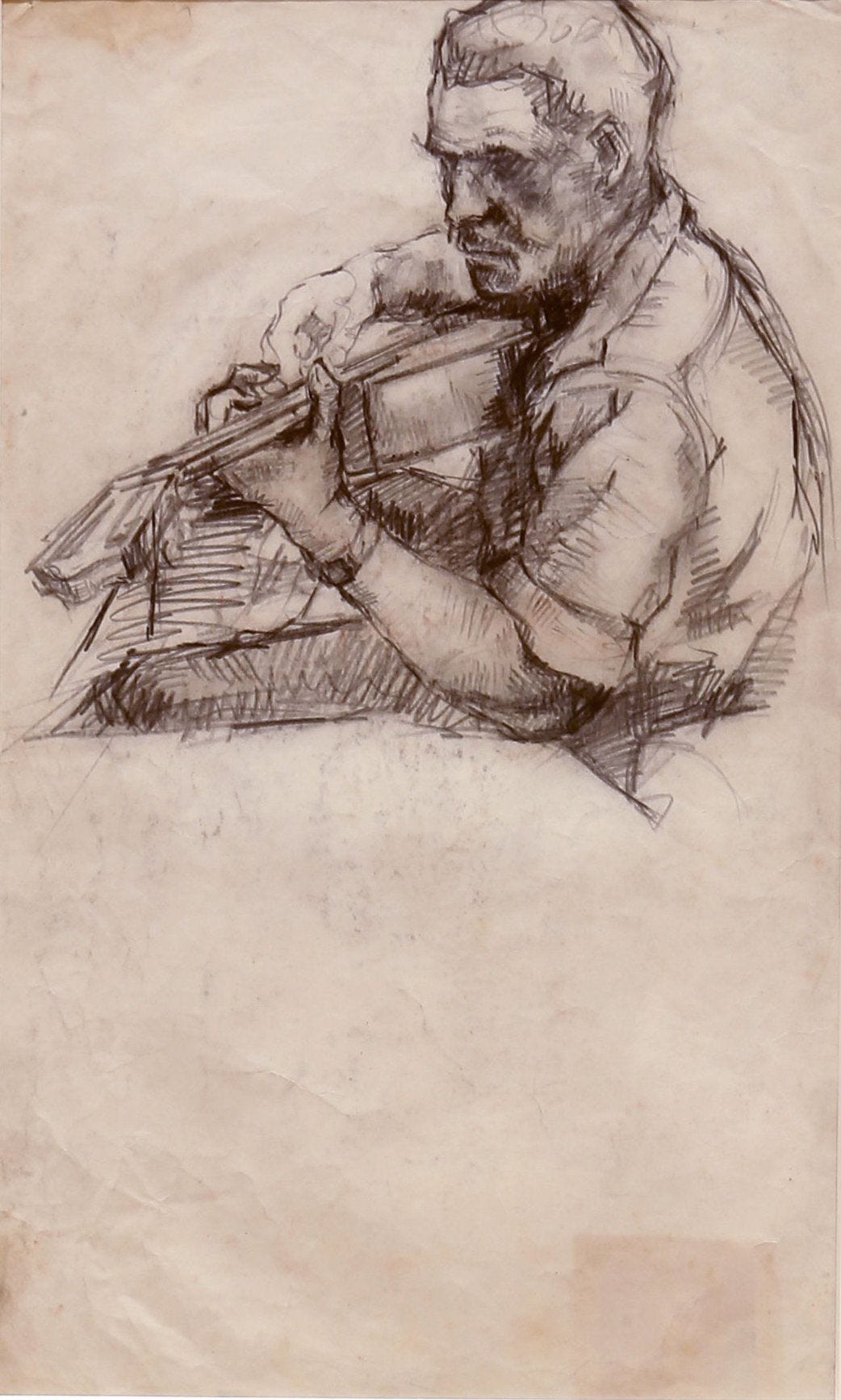

Jack Martin Rogers (late father of the gallerist). “Uilleann Piper” (c. 1981). Pencil on paper. On view in “Jack Martin Rogers: Drawing” at Anita Rogers Gallery.

Faithful collectors have made some purchases, but sales are quiet for the most part. When locals return to the city—which Rogers thinks will take time, with schools mostly remote or part-time—she expects the market to return to normal in stages.

“In my experience, hardcore New Yorkers find it difficult to be away for prolonged periods, so I do expect the city to repopulate downtown—but not to its usual capacity,” she said. In subsequent stages, those moving into new homes in Connecticut and New Jersey suburbs will need art for their more-expansive walls. That will facilitate sales, Rogers thinks, until openings and parties return to normal in New York and California after a vaccine is readily available.

Nothing could convince Rogers to relocate the gallery from her current 3,200-square-foot location, though. “I still feel downtown New York City is where it is at for the New York art world,” she said. “A long history, the architecture, and the loft buildings keep that statement true, and Chelsea has been breaking down for some time, with quite a few galleries moving to Tribeca or the Lower East Side.”

Jack Martin Rogers. “Man with Guitar” (c. 1965). Pencil on paper. On view at Anita Rogers Gallery.

Although many art collectors, who have bought larger properties outside New York, will likely stay away until there is a vaccine, Rogers expects that some “less hardened” New Yorkers will remain in the suburbs for good. She hasn’t heard of art-world colleagues discussing abandoning ship yet.

“I don’t think we’ll see the massive fallout in the gallery world until 2021, when commercial landlords will start to get more aggressive on rents, and galleries won’t be able to pay those rents,” she said. “I foresee many more galleries closing, sadly. Not us! We are safe.”

Rogers is currently showing her late father’s (1943-2001) architectural and figurative art in “Jack Martin Rogers: Drawing.” The British artist’s preparatory drawings reflect his “immense dedication to observation and detail,” according to the gallery website. He dissected bodies and sketched them while studying anatomy and fine art at the Birmingham School of Art in the UK, the site adds.

Much of the artist’s oeuvre was lost in a 1984 fire in Turkey, and some of the surviving works have burn marks. In addition to drawing and painting, the late artist was also a musician designed and build his own instruments.

Jack Martin Rogers. “Anita” (1994). Pencil on paper. On view at Anita Rogers Gallery.

Among her father’s subjects was Rogers herself, whom he painted as both a child and a teenager. “One beautiful painting of me and a rocking horse was sadly burned in the fire that destroyed our home in Turkey,” she said. “We do have one sketch he did of me in 1994 in the current show.”

Asked to describe her father in brief, Rogers called him “brilliant and a renaissance man,” who was a very-talented musician. “He played the lute—and made a lute—classical guitar, lute, Greek traditional bouzouki, and sang, and all to perfection,” she said. “He was completely dedicated to being an artist and committed to being a fine draftsman. He was a perfectionist and extremely hard on himself.”

Rogers figures her late dad wouldn’t have allowed her to hang all the works that are in the current show, were he alive today.

Growing up, Roger’s dad, who lived for his art, traveled around Greece and Turkey with Rogers (who was homeschooled) and her mom in a Volkswagen camper van. “His goal was to keep us as free as he could from being chained to a system,” she said.

“Dad was a sensitive and compassionate person and a wonderful father and husband,” she added. “I remember him wishing he wasn’t so sensitive, so he could put his art before family, but he could not!”

One memory of the music and dance that always surrounded Roger’s dad was a time when they played for more than 24-hours straight on the Greek island of Kea. “The village residents and tourists were dancing all night,” Rogers recalled. “It all started with just a Greek priest and six fishermen drinking beer in the afternoon who spotted Dad’s bouzouki. It grew from there.”

Jack Martin Rogers. “Man” (1977). Graphite on paper. On view at Anita Rogers Gallery.

It’s bittersweet to show her dad’s work, and Rogers thinks he would be proud to know his art was on exhibit and would love the architecture of the gallery (especially its 17-foot ceilings). “I just wish he was alive to enjoy it with me,” Rogers said. “Some of the pieces are for sale but only a few. Most of the pieces I would refuse to part with.” She would consider selling some to certain museums, though, as she wants her dad’s art to be seen.

Galleries like Rogers’ also support living artists, which is vital when so many are suffering financially in an uncertain art world.

“I would emphasize to people the importance of supporting your local, living artists during these unstable times,” she said. “Art is food for the soul and during a time when the world is on edge, art can do wonders.”

“The current reality is people are afraid to enter spaces with potential crowds, and although online helps, nothing is a substitute for engaging with a piece of art in-person,” she added. “I can’t wait for life to feel safe again, and safe for buyers, supporters, and viewers to comfortably enter into gallery spaces.”