...Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of (kosher) rum!

An interview with Arnon Shorr, author of the graphic novel “José and the Pirate Captain Toledano” and director of the film “The Pirate Captain Toledano.”

I have known Arnon Shorr since grade school. He is a filmmaker, screenwriter, and more recently, a graphic novelist. “But since our jobs shouldn’t define us, I’m also a father, a Jew whose practice could best be described as “vaguely Orthodox”, a coffee snob, and an amateur astrophotographer, among other things,” he informed.

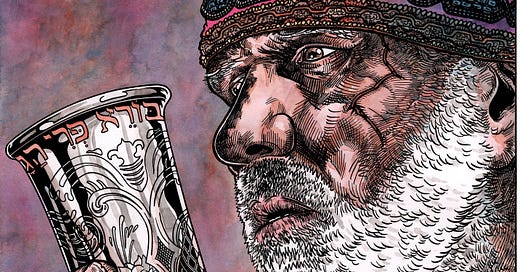

I posed questions to Arnon about two new projects of his that relate to Jewish pirates: the film “The Pirate Captain Toledano” (IMDB and Amazon Prime Video) and the graphic novel “José and the Pirate Captain Toledano” (Kar-Ben Publishing, May 1, 2022, illustrated by Joshua Edelglass). I have edited some of the responses below very lightly for style only.

Rough Sketch: I thought two of the 10 Commandments prohibit stealing and killing. How could there be Jewish pirates?!

Arnon Shorr: Are we (Jews) human? Or are we some sort of ‘not quite human’ race held to a different standard than everyone else? No one asks, “How could there be Christian pirates?” or “How could there be Muslim pirates?” Why should we accept the question “How could there be Jewish pirates?” unless we somehow accept the notion that separates Jews from everyone else (which is the notion that allows for the possibility of persecution).

RS: When did you first realize there was such a thing as Jewish piracy, and what drew you to this subject as fodder for a film and a book?

AS: I learned about Jewish piracy from a friend of mine, who recommended the Ed Kritzler book, “Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean” (2009). I found the book fascinating for many reasons, but what drew me to tell a Jewish pirate story was the realization that Jewish piracy opens up an entirely new dimension to popular pirate mythology: Typically, pirates in fiction operate based on greed or a lust for adventure. Piracy is—ultimately—selfish. Jewish pirates operate with a motivation that is entirely novel in pirate folklore: vigilante justice.

As refugees from the Spanish Inquisition, they prowl the seas in search of Spanish ships—ships that were paid for in large part with plundered Jewish wealth. The piracy genre has been around for a while, so it’s hard to find a new story to tell. (“Pirates of the Caribbean” had to resort to supernatural mythology to give those films a new twist.) But it seemed that I had stumbled upon one of the biggest possible innovations in the pirate genre since Robert Newton used a Cornwall accent when he played Long John Silver in “Treasure Island.” Of course, vigilantism isn’t justice, but it’s an attempt at re-balancing an unjust world. That motivation opens the door to a huge range of new pirate stories unlike any we’ve seen in the genre.

RS: From the bit that I understand about piracy, it was historically rather different than the way it’s portrayed in “Treasure Island,” “Pirates of the Caribbean,” etc. Jews too have been rather misunderstood over the centuries (sometimes qua honest mistake, other times neither honest nor mistaken). Is Jewish piracy a kind of marriage made in heaven in a kind of way then?

AS: I’d like to think there’s a lot of valuable overlap—at least when it comes to narrative fiction—between pirates and Jews. Pirates are, by nature, drifters, or wanderers. They seek safe havens where they can find them, and operate by codes of honor and codes of conduct that seem mysterious to outsiders. So, yes, I think that there’s a way to see Judaism and Piracy as strange reflections of each other. (Reflections in a funhouse mirror, to be sure!)

But really, it’s not so much the blending of Judaism and piracy that captivates me. It’s the blending of Jews—specifically Sephardic Jews after the Inquisition—and piracy, specifically piracy against Spanish ships. It’s the combination of historical circumstances that makes these pirates especially fascinating to me.

RS: What were some of the challenges and opportunities visually and textually here when you approached this story in film and in print?

AS: The challenges to pulling an independent film together are more numerous than I could list—even for a short film such as mine! Most of those challenges are quite mundane, and boil down to a version of just one question: How can we squeeze so much storytelling out of so little money?

But there were some very interesting challenges, too, especially where it pertained to the question of historical authenticity. For example: In the film, one of the characters recites a Friday night Kiddush. I wanted to know: What melody would a Sephardic Jew have used for Kiddush in the 16th century? Are there any traditions that go back that far? My inquiries led down a fascinating rabbit hole of old Sephardic music.

We know some old tunes, but it’s very hard to pin down exactly how old a tune is, because so much of the music was not written down until centuries after the expulsion. Eventually, I was introduced to members of the Spanish Portuguese Synagogue in New York, who directed me toward a very old cantorial recording of the Friday night Kiddush. Was that melody used in the 16th century? No one knows. Its origins are lost in time. But it’s a haunting melody, so that, combined with the mystery of its provenance, was sufficient for me. It would serve the dramatic moment well.

RS: What do you hope viewers and readers will take away from this project?

AS: First of all, I’m a very big believer in the importance of ‘entertainment value’ in art. I don’t see much distinction between a work of art and a work of entertainment. So I hope viewers and readers come away from my work entertained. The book, in particular, is a swashbuckler. There are naval battles! Sword fights! I mean, there’s drama! Of course I hope all that stuff makes your heart pound and makes you turn each page with just a little bit more urgency.

But I also think there’s meat on those bones. For Jewish readers, I hope the book prompts questions about the roles that ritual and language and knowledge play in our Jewish identity. What does it mean to be Jewish if you don’t know Judaism? What does it mean to be part of this particular Abrahamic tribe?

And for a broader range of readers, regardless of their faith or heritage, I think of the book’s third act as a sort of window into an alternate universe, from which we all might learn something. In that third act, we discover that the pirates on Toledano’s ship all have a variety of backgrounds and histories and places they’ve come from and things they’ve lost. And yet, as different as they are from each other, they’re all pirates of the Laqish, working together, living together.

Perhaps I’m too optimistic, but I see that as a model we might be able to replicate in the real world. On the Laqish, difference is the norm. Perhaps we should see our own world this way, too?

RS: So much of Jewish art and literature (and history)—at least up until 1948—shows Jews as victims and in a state of powerlessness. You’ve also told a story of Jewish persecution, but also of a rare power. What, do you think, does this mean?

AS: All of the stories we tell are important. I need to state that outright because I don’t mean for my critique to diminish the significance of stories of victimhood. “We were all Slaves in Egypt!” one might declare. And there are lots of good reasons to tap into that narrative and into subsequent narratives of persecution. Perhaps they make us more cautious? Perhaps they make us take better care and become more resilient? Perhaps they make us more sympathetic—or empathetic—with those people who we are morally and religiously impelled to care for? Those are incredibly important reasons!

But I suggest a different (and additional) reading of the classical line that prompts this idea: “In every generation, one must see himself as if he left Egypt.” As if he left. That is to say, as the triumphant one. The victor. Not as the slave nor the victim. It’s important to see ourselves as heroes, too. Because if we see ourselves as heroes, we might be inspired to more heroism. If we see ourselves as triumphant, we might strive toward more triumphs, rather than resigning ourselves to infinite persecution (or inevitable defeat).

There’s another layer to this, and it comes into play when folks outside the Jewish world encounter this story (as many did with the film—it played in places like Helper, Utah and Tetovo, Macedonia—places with no real Jewish presence at all.)

When the stories that we project about ourselves hit one note over and over and over—in the case of depictions of Jews and Judaism in popular American media, the opaque Chassid or the angsty, secular New Yorker, all Holocaust survivors or the heirs to that generational trauma—what happens to the way we’re perceived?

Jews make up a tiny fraction of the U.S. population, so it’s pretty safe to suppose that most Americans don’t know any Jews. It’s possible that many Americans have never even interacted with one. If all they get is this one-note narrative, it’s bound to raise suspicions. It’s not enough. It’s not the whole story! There’s got to be more to Judaism than secular angst and the Holocaust.

But absent of further data (since actual Jews are scarce), it’s natural for people to fill in the blanks, themselves. Anti-Semitic ideas tend to fill that vacuum, and they fill it quickly. So I think there’s a really important reason to tell stories that ‘buck the trend’ and expand the palette of Jewish characterization in popular media. Stories that depict Jews that are untouched by (and not defined by) the Holocaust. Stories about Jews who are not angsty, nor ambivalent about their faith or traditions. Stories about Jews who are not doctors, lawyers, nor movie producers. These all take up space in the public imagination that would otherwise be filled by the stories our detractors make up about us.

I had an unsettling (but not surprising) experience when I raised money for the short film. It was early in my research about Jewish pirates. I put the term, “Jewish pirates” into Google and browsed the results. It wasn’t long before I hit the inevitable: The term was not used to describe historical figures. It was a slur. And some bloggers at the time had even taken the bits of history that they could find about real Jewish pirates and used it as “evidence.” ‘See, the Jews are really just gold-greedy thieves!’ When we don’t tell our story, they tell it in their own way.

So, part of what I’m trying to do with this narrative—whether it’s in the short film or in the book, or in whatever future iterations unfold from it—is to reclaim this narrative as one we can be proud of, rather than allowing it to be co-opted by those who’d rather slander us than learn who we really are.

RS: Here, again, are the links to the film and to the book.