A very timely Judaica auction

Kestenbaum’s sale of printed books, manuscripts, and graphic and ceremonial arts is slated for July 21.

Among the offerings slated for sale in the July 21 Kestenbaum & Company Judaica auction are several objects that speak directly to current concerns even if they’re more than 150-years-old. They include:

A 1785 book by Jewish physician Abraham Nansich-Hamburger presenting rabbinic direction allowing smallpox inoculation ($500-$700)

An 1855 Hebrew-and-Italian text which includes a prayer to halt an 1836 epidemic ($1,000-$1,500)

An oil-on-panel painting depicting English police surrounding a rally supporting convicted (later executed) Jewish spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg ($800-$1,200)

Seven letters (1848-55) which immigrants sent back to Germany, including one that refers to southern slave-masters treating enslaved people as dogs ($1,500-$2,500)

A 1915 lithograph poster depicting an allegorical figure of America offering bounty to a poor Jewish family ($3,000-$4,000)

(Left) Abraham Nansich-Hamburger’s “עלה תרופה” (“Leaf of Healing”). 1785. Lot 164. Auction estimate: $500-$700. (Right) A.V (Abraham Vita Chai) Morpurgo & A. Luzzatto. “תפלה לעצירת המגפה” (“Prayer for the Halt of the Epidemic. Recited by the Jews of Trieste during the Invasion of Asian Cholera”). 1855. Lot 165. Auction estimate: $1,000-$1,500. Kestenbaum & Company.

“That’s precisely why I sought these items out and placed them in the sale at this time,” Daniel Kestenbaum told this newsletter, of the objects’ timeliness.

Of the 1855 “Prayer for the Halt of the Epidemic. Recited by the Jews of Trieste during the Invasion of Asian Cholera” by Abraham Vita Chai Morpurgo and A. Luzzatto, the auction house notes 1.5 million people globally died from the third cholera pandemic (1852-60). The casualties included Jewish victims, including Trieste leaders. (Note to those uncomfortable with the reference to “Asian Cholera,” that’s in the original title.)

The auction notes add:

It was during the course of this particular pandemic that both R. Akiva Eiger and R. Israel Salanter took radical Halachic [Jewish legal] steps to demonstrate the importance of preserving life by insisting on social distancing even if that would hinder communal prayer services. A Halachic position that has significant influence amidst the current coronavirus crisis.

Among the 220 auction lots, several other objects struck me, although there are too many interesting tidbits and stories about them to detail in full. The entire catalog is worth a look, if one can spare the time.

Detail of silver filigree spice container. Germany/Galicia, mid-18th century. Lot 6. Auction estimate: $150,000-$250,000.

A mid-18th century, German silver spice box is particularly beautiful for all of its varied and intricate elements, including human figures (one load-bearing, Atlas-like below), clock faces, angels, bells, instruments, and hinged doors.

A “most unusual” nautilus shell (c. 1900, $3,000-$4,000) is decorated with a Sacrifice of Isaac, the Jews Free School of London, and the Hebrew inscriptions “Blessed are you when you come in, and blessed are you when you go out” and “Praiseworthy is he that considers the poor. God will protect him in difficult times.”

An English inscription notes that the entire object was engraved “with a common penknife.” Though the artist is unknown, “He likely was Jewish due to his skilled use of Hebrew,” Kestenbaum said.

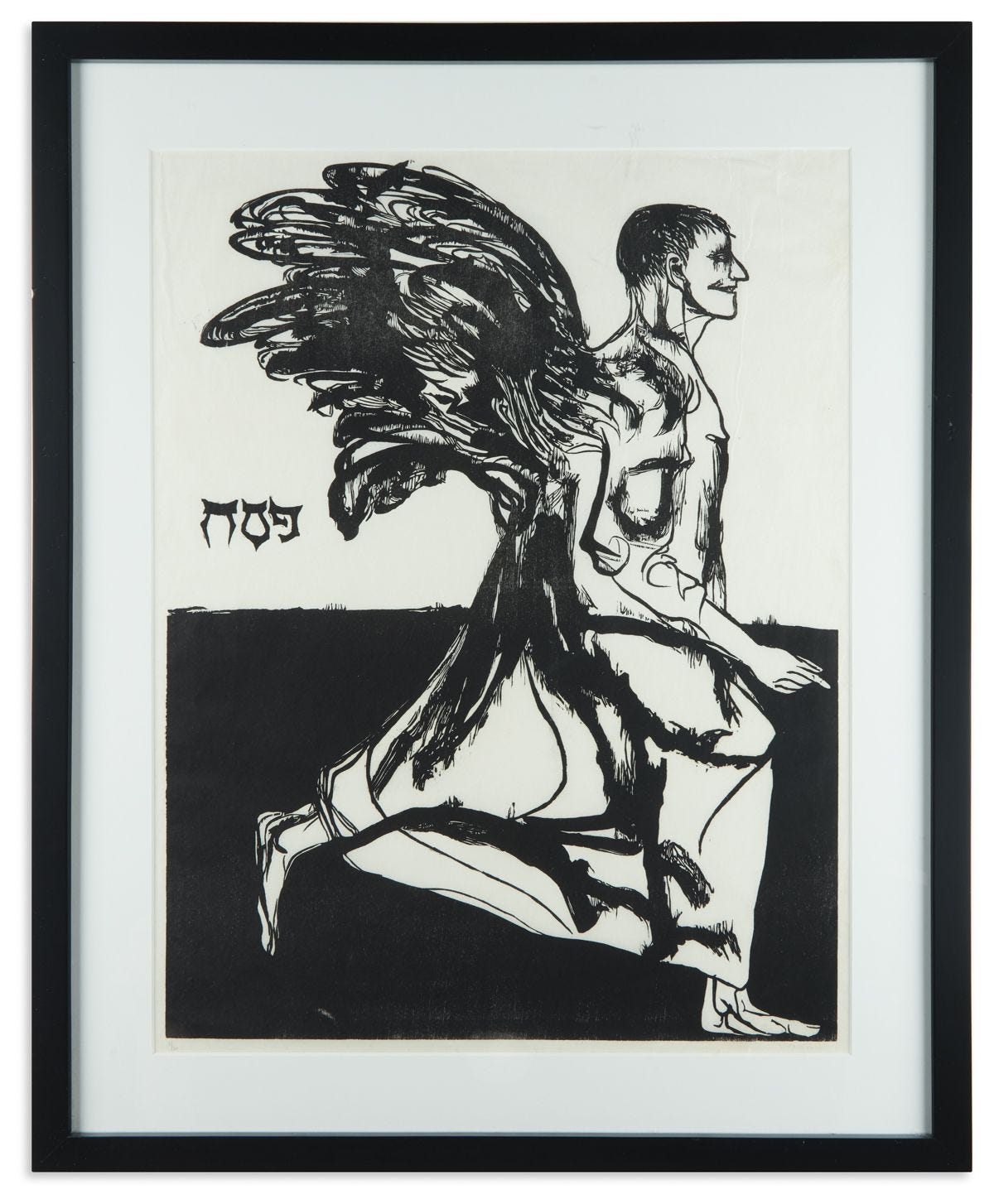

Four other works stood out to me: A portrait of a bearded rabbi by Gerbrand van den Eeckhout (1624 -74), a student and friend of Rembrandt’s ($20,000-$30,000); the painting “Jewish Scholars” (c. 1900) by Austrian artist Bernd Werner, who often painted Jewish subjects ($2,000-$3,000); a Leonard Baskin woodcut ($500-$700) titled “Passover,” likely depicting the Angel of Death; and a 1703 satirical work purporting to be the biblical Haman’s will ($500-$700).

Leonard Baskin. “Passover.” Woodcut. Lot 39. $500-$700.

Haman, the Book of Esther villain, tries to arrange for the murder of all of the Jews in king Ahasuerus’ vast kingdom. Instead, he and his sons are hung and the Jews saved. If Haman had drawn up a will, it wouldn’t have mattered, as Ahasuerus overrode it and turned his belongings over to Esther and her uncle Mordecai.

In this version, by David Raphael Polido, two satirical witness names are affixed to what may be history’s first satirical ethical will. Among the word plays is Haman’s soul being bound for “Me’arat ha’afelah” (dark cave), a take on “Me’arat ha’machpelah,” the patriarchs’ cave where Jewish tradition holds that Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and Jacob and Leah are buried. Per one description of the work:

Haman is described as lingering in prison, awaiting execution. Meanwhile he calls his family to his side and reads them his Testament In language which parodies in part the Blessing of Jacob (Gen. 49) and in part the Ten Commandments, Haman admonishes his children to live peacefully among themselves, and to unite in their hatred against the Jews. He also advises them to have no mercy on the poor, to abstain from the practice of charity, because it is profitless, to threaten their creditors with violence if they importune, and on the other hand, to give their debtors no rest if they refuse to pay promptly, Finally, he urges them not to steal from the poor, because they possess little that is worth stealing. Such, according to the parodist, are the Ethics of Haman.

Satirical takes on biblical tragedies might be just what the doctor ordered—along with “social distancing” dating back to 1855.